77: Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse #Newbery100

- Sara Beth West

- Apr 7, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Jul 3, 2021

2022 will mark the 100th anniversary of the Newbery Medal. In honor of this momentous event, I launched a project to read through each award-winner, starting with some background on the award and with commentary on the first medal winner: The Story of Mankind by Hendrik Willem van Loon. Today I take up the 77th recipient: Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse.

By 1998, the traditions around the awarding of the Newbery Medal had been long established. A selection committee, all members of ALSC (a division of ALA), works tirelessly all year to read and evaluate the wealth of books published for children in that year. The final decision is made through often grueling meetings during ALA Midwinter and announced on the final day of that conference. In 1998, the committee chose the following:

Winner:

Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse (Scholastic) Honor Books:

Ella Enchanted by Gail Carson Levine (HarperCollins)

Lily's Crossing by Patricia Reilly Giff (Delacorte)

Wringer by Jerry Spinelli (HarperCollins)

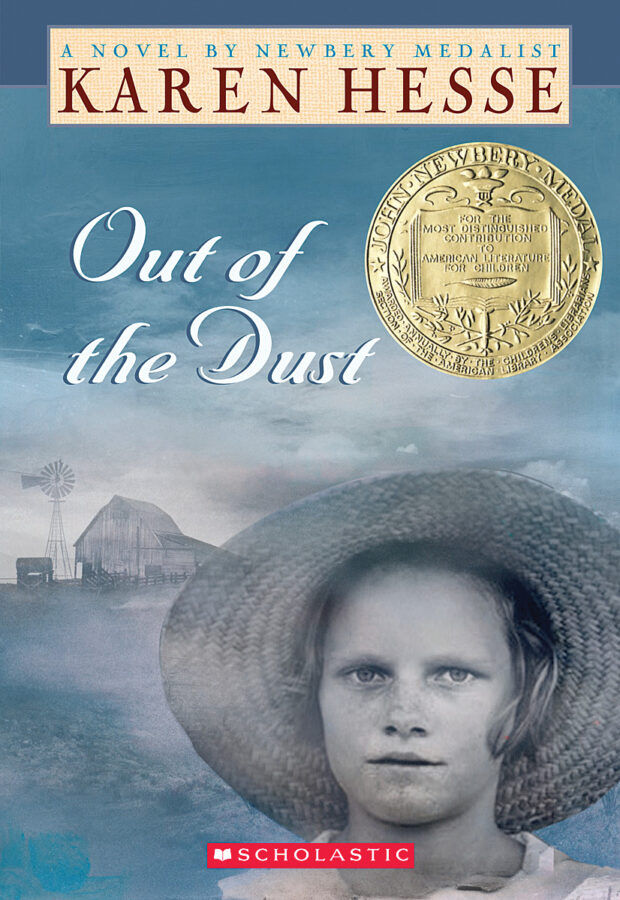

Out of the Dust is a novel-in-verse set between January1934 and December1935 in the dust-covered plains of Oklahoma. This work of historical fiction was inspired by a photo (shown on the cover) taken by FSA photographer Walker Evans. Despite Dorothea Lange's work capturing the Dust Bowl and its effects, the photo that spoke to author Karen Hesse is from Evans' work with James Agee in the deep South, collected in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Regardless of her origin, the determination and spirit of Lucille Burroughs (the girl Evans photographed) is what led Karen Hesse to tell the story of Billie Jo Kelby.

Billie Jo is 13 when the book opens, "a redheaded, freckle-faced, narrow-hipped girl" living with her father and mother, who is finally pregnant after years of trying. The book also opens in the middle of terribly hard times on their land. Weeks of drought get broken by days of rain too hard to do anything but damage, and the Kelbys and their neighbors are just barely getting by. But Billie Jo has her music, the piano she and her Ma both have such a talent for, and the money from President Roosevelt's loan program gets them through the worst. Until the real worst happens: a pail of kerosene that Ma mistakes for water leaves both Billie Jo and her Ma burned badly, and after days of suffering, both Ma and the baby die, leaving Billie Jo alone with her fire-ravaged hands, her Daddy, and her anger at him for leaving the pail there by the stove.

The rest of the book does the work that Hesse says is the point: forgiveness. In her acceptance speech, she explained:

It was about forgiveness. The whole book. Every relationship. Not only the relationships between people, but the relationship between people and the land itself.

Over time, Billie Jo learns to forgive her father and herself. She wants nothing more than to escape the dust until she hops a train one day and does it, only to turn around and come right home again. She even forgives the land for being so unforgiving, loving it despite the hardship it brings.

Though it is common enough now, the novel-in-verse was a "new phenomenon in the world of children's literature," according to Joy Alexander. Her 2005 examination of the genre provided a half-dozen or so examples of the form from 1993-1996 with more starting to emerge in 1997. Though not the first, Out of the Dust quickly established itself as a standard-bearer for the form, a position it held for many years. Alexander explains, "in two respects Hesse expands the genre in new directions. Her fiction is based on historical events, so that personal narrative is carefully anchored in place and time and moves toward documentary." The other way Hesse's work stands apart, according to Alexander (and, I would presume, the Newbery committee), is the lyricism of her words.

As a vehicle for a first-person narrative, a novel-in-verse is excellent for the immediate and realistic rendition of voice, but it can devolve into teenage melodrama without a great deal of care. Hesse set the bar for that kind of care. Whether describing the natural surroundings, as in "First Rain,"

I hear the first drops.

Like the tapping of a stranger

at the door of a dream,

the rain changes everything.

It strokes the roof,

streaking the dusty tin,

ponging,

a concert of rain notes,

spilling from gutters,

gushing through gullies,

soaking into the thirsty earth outside.

or the unexpected joy at "The President's Ball,"

Tonight, for a little while

in the bright hall folks were almost free,

almost free of dust,

almost free of debt,

almost free of fields of withered wheat.

Most of the night I think I smiled.

And twice my father laughed.

Imagine.

Hesse employs the art of free verse while maintaining Billie Jo's voice, like a note struck pure and true. And as Alexander explains, somehow Billie Jo's single voice "allows for a greater sense of outer life along with a deep understanding of the narrator." It is always personal, always through Billie Jo's lens, but her gaze captures the whole of her community and shares it lovingly.

In her acceptance speech, Hesse says she never questioned that this book was to be in verse, even though she had left poetry behind as she entered the years of motherhood. And it is this, I must confess, that stuck with me long after I had forgotten the beauty of the language and the story of this family's tragedy. She said,

Part of my mind always listened for my children during those years. And that listening rendered me incapable of writing poetry.

Years after this Newbery medal was awarded, when I had two small children of my own, I would think of these words and the promise they held. The assurance that listening for my children was its own kind of creativity carried me through the years of little writing, and like Hesse, I have found that children will grow, and the words do return. I know this means nothing to the children who are the intended audience of this book, but it means much to me.

But what of those child readers? Where does this book stand for them? I imagine it is accessible though not always engaging. Like so many titles, it likely finds its perfect readers and leaves others cold. Historical fiction is not every young reader's preference, but for that -- and for the hard, heart-heavy stuff -- Hesse refuses to apologize, insisting:

Young readers are asking for substance. They are asking for respect. They are asking for books that challenge, and confirm, and console. They are asking for us to listen to their questions and to help them find their own answers.

and

Historical fiction ... helps us understand that sometimes the questions are too hard, that sometimes there are no answers, that sometimes there is only forgiveness.

Two of the three honor books from 1998 are fairly forgettable titles from well-celebrated authors. Gail Carson Levine's Ella Enchanted, a fantasy retelling of Cinderella, has remained beloved, so maybe Hesse was only half right. Though her book might not be right for every reader, she is responsible for the launch of a form that has excelled itself countless times, from Elizabeth Acevedo to Nikki Grimes, Kwame Alexander, and countless others. For that, as well as for her words, I am grateful.

Comments